Dhalgren by Samuel R. Delany

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

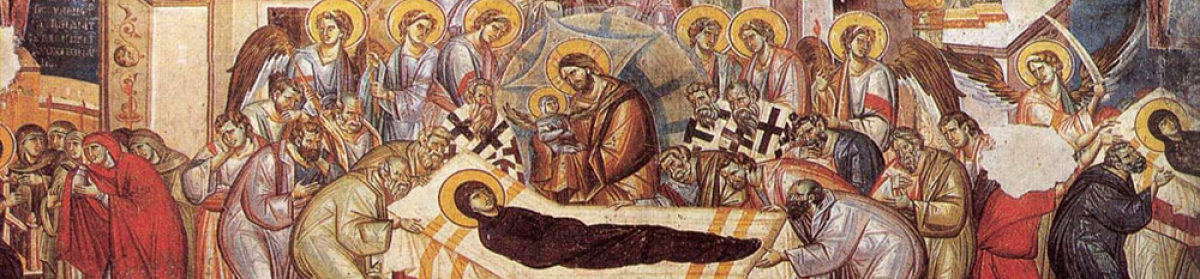

This is one of those books that is both influential and rarely read. It is a long book, full of fascinating characters and interesting events. The people are complicated, as is the plot. The book is set in the fictional midwestern town of Bellona, a place where the laws of nature and the norms of behavior are both broken on a regular basis. The rest of the world seems to know Bellona exists, and the strangeness of the place, but seem to do nothing about it. There is a central mystery to the place that drives the plot forward, yet this MacGuffin is never explained. This mystery is mirrored by the central character, a man who has forgotten his name, and so is called the Kid. The closest to an explanation we ever get is near the end, when the Kid remembers part of his name, but not his family name. Likewise, at the end of the book, it appears that the outside world is bombing Bellona, and a number of the characters escape the same way they came in. As the Kid is leaving, he meets a couple of characters heading into Bellona, an event which is similar to the opening events of the book. This sense of the book circling in on itself is seen in the way the opening line of the book (to wound the autumnal city) is a continuation of the closing line of the book (Waiting here, away from the terrifying weaponry, out of the halls of vapor and light, beyond holland and into the hills, I have come to). The book is like a Mobius strip, a mathematical concept called a torus, or like the image of a snake swallowing itself. It hints at the story being endlessly repeated, only with different characters each time, each taking the same journey. Kind of like life.

Dhalgren bears a family resemblance to Jewish Second Temple apocalyptic literature, in which a person takes a journey through another, higher reality, one where judgment and reward are tied to the end of days. The New Testament book of Revelation is similar to Dhalgren in that time is not linear, but elliptical. The same events happen over and over but are described in different ways. The kid’s journey through the town of Bellona is likewise filled with apocalyptic portents. The kid escapes destruction, just as a new set of travelers arrive to begin their own personal journey through Bellona. There is a sense that destruction is always imminent, one the kid barely escapes. And yet there is also the sense that each traveler’s journey is unique, and that as long as there is one more new traveler, Bellona will not reach its teleological end.

Having said all that, the book is full of violence and sex of the type that would have gotten the book banned in an earlier era.

View all my reviews