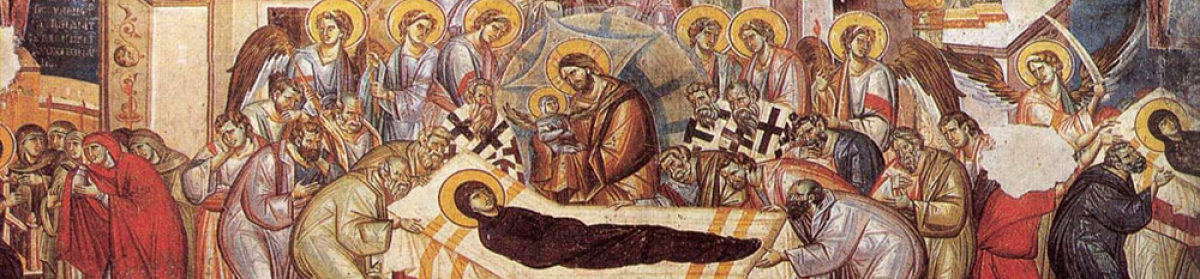

by

Leonid Osipovish Pasternak

Don’t let anyone kid you — writing any book is hard work, but writing non-fiction can be harder. (Although not working in an iron foundry hard, so perhaps difficult would be a better word.) Most books, courses, and workshops on writing are geared towards fiction. I am unable to write fiction, and when I attend writer’s workshops I feel like an orphan. The Creative Writing types seem to look down on non-fiction writers, as though it is a lesser, more formulaic type of writing, as though making a topic interesting for the reader doesn’t require skill and creativity.

Being a non-fiction writer can be quite rewarding. Not in a financial sense, although that is always part of the plan. But there is real satisfaction in exploring a topic, finding connections between seemingly disparate facts, and learning something new. The creative juices get flowing when the writer finds a new angle on the topic and puts a new spin on the presentation of the information.

But first, where to begin? With a question that requires an answer. Sometimes you can formulate the question quite precisely, in which case an Internet query can provide the answer. But sometimes you are curious about a topic, and you don’t know enough to ask the right question. That is where the research begins. You piece things together, following the trail of breadcrumbs from place to place. A search of the Internet can turn up a range of opinions and documents on various topics, so you’ll want to explore alternate points of view. Avoid blog posts which are nothing more than personal opinion. Instead, look for someone with scholarly pretensions, someone who provides sourced quotes, someone who at least mentions alternative points of view and someone who cites their sources. Then, follow those sources. If you are using a journal article or a book, always check the footnotes, as they can lead you to interesting sources and provide fascinating detail. Primary (or original) source material is best, but is not always available, especially if it is in a foreign language or locked behind a paywall. In that case, you may have to use secondary source material, so try to use the best and most generally accepted source material available.

I usually write several short papers to keep track of my research and collect my thoughts. Sometimes the writing begins with a passion and the pages seemingly write themselves. But most of the time writing is not about inspiration, but about pushing through the drudgery hoping for the next burst of inspiration. Sometimes the words will flow, but most of my time is spent wrestling the text into shape. After some time I get a sense of where the research is heading, and sometimes is going in an unexpected direction — which is a good thing. This tells me my thinking is no longer bound by my preconceived notions. When I am willing to examine and possibly even accept alternate points of view, I am intellectually invigorated. When a new interpretation of the facts provides a fuller explanation, and when I can accept that with an open mind, I’m am altering my mental framework, something necessary to get a new angle on the subject.

If you chose to follow this process, eventually you will have done enough research to get a handle on the topic and begin refining the research question. At this point you likely have done enough work to produce an outline and should begin plugging your research under the appropriate headings. Once you’ve done that, you’ll have an idea of where the holes are in your research, and you’ll have a pretty good idea of the work remaining.

I have found I can do forty pages without too much trouble, but getting over that can be a problem. For my first book, I ended up dividing the book into multiple parts and worked on each of them individually. This worked for a while until I began having some overlap between the writing. I found I had begun going over the same topics again, addressing them in a different context. That is when I began to make some hard decisions when I really began to wrestle with the text.

Any number of book reviews will complain about a book being repetitious. This can be true, but I’ve also noticed that books can suffer by avoiding a previously mentioned topic. Just because a topic has been mentioned in one context doesn’t mean the topic isn’t germane in a new context. In my opinion, readers don’t want to have to flip back several chapters to figure out what you are talking about. To me, a degree of repetition is respectful of the reader. On the other hand, simple repetition is a sign of a sloppy mind. When I find I’m just repeating myself to no good purpose, one of the passages has to go.

One of the hardest things about writing is eliminating your own writing. It’s a Sophie’s Choice, which is why writers call it “killing your children”. It’s always a judgment call, and a writer is not always the best judge of their own work. This is where an editor is helpful. Give your text to someone and listen to their feedback. Don’t argue with them, or you won’t get honest criticism. If they are your intended audience and they don’t understand something, you need to simplify and clarify your writing. If the subject has its own jargon, you might need to explain what the words mean. Sometimes this can be done inline, and sometimes in a footnote. Although a glossary is often necessary, be respectful of your reader and define your terms as you use them. (Someone complained about all the big words in my first book and suggested the addition of a glossary. I’m working on that for the next edition.)

Simplify, simplify, simplify. Less is more. Avoid adverbs as much as possible. Don’t begin or end sentences with prepositions. All such maxims are good advice and should be kept in mind. But they don’t always apply. I like complex sentences, full of parenthetical detail and such. It’s the way I talk, and the way I think. I will try to edit these into simple, terse sentences, but sometimes it isn’t possible without doing damage to the sense of the text, without losing it’s meaning, and without destroying the rhythm. Good prose writing has a structure, a rhythm, a beat. Sometimes a big word is better than a short one at expressing your point, and sometimes it just fits the structure of the sentence. Other times it is just pretentious. Use your judgment, but follow the advice of your readers and editors as much as possible.

Another source of drudgery is the formatting of your book. So many decisions to make.

- Which Style Manual to use? Some specialized fields have their own style manual, which makes the choice easier. I personally use the Chicago Manual of Style; even with its flaws, it remains one of the most useful and comprehensive style manuals on the market. (If you are self-publishing, the “Parts of a Book” section is worth the price of the book. You’re welcome.)

- Footnotes vs. endnotes? And if you use endnotes, do you put them at the end of each chapter? Each section? Or at the end of the book? How do other books in your subject area handle these?

- What font should you use? Do your research on this, and take your time. Don’t use a font created for the web (like Verdana), because it won’t look as good in print. For an ebook, you probably want to use a sans-serif font. For print, use a serif font. Use different but related fonts for your body and headings.

- The more academic your book is, the more you will need an index. Even though modern word processors will automate much of the processes, it is still a long and laborious process.

- If your book is in a specialized area of research, you will need a glossary.

- You need to decide on the size of your printed page. Take a look at other books similar to yours, and choose a similar paper size. Many books use 6″ x 9″, and some self-publishers recommend this size. I found that my page count exploded once I switched my manuscript from the standard 8.5″ x 11″ format, so you might want to change your page layout early in the process.

All of this seems unconnected to the creative process but has everything to do with making your writing useful to the reader. Whether you do it yourself, pay someone to do it, or if your publisher does it, it still needs to be done. Call me a control freak, but I prefer to do it myself.

So how long should your book be? The ideal book length (from the standpoint of a publisher) is 288 pages. The reason is that all the pages can be printed in one shot with no wasted paper. 288 pages is less costly for printing, binding, packaging, and shipping. The longer the book, the more expensive it is to produce, which is a factor for both the traditional publishing house and a self-published book. And the more expensive the book is to produce, the more the end customer has to pay. From a word count perspective, the writer should aim for 80,000-89,999 words. If your book is shorter than this, you may not have done enough research; if longer than this, you may need some ruthless editing. If you are well over this word count, some suggest you think about dividing your book across multiple volumes. Also, different types of writing have different expectations for the length of a book. Adapt accordingly.

With my first book, I kept writing until I got to over 500 pages (at 6″ by 9″), at which point I went back and ruthlessly cut out over 100 pages. Which was a good thing, because the index and the bibliography added many additional pages back into the book. The published product wound up at 452 pages. I’m not happy about the length, but it is as short as I knew how to make it. I originally tried to stop once I’d reached the 288-page mark, but there were still holes in the research. A shorter book would not have answered the research question I’d given myself. Having written the first book, I find my second book is more likely to come in near the ideal length.

So when is your book done? This is a good question, and somewhat related to the length of your book. I found that once I’d filled in my outline, connected all the dots, and made everything flow well from one chapter to the next, I was still nowhere near being finished, and that the writing and editing process seemed endless. There was always one more source to track down, one more quote to add, one more idea to explore. But eventually, the process started to slow down. Once I realized I was spending more time polishing the prose than writing, I began to suspect was nearly finished.

Once you’ve reached this point, put your book away. Avoid it, don’t look at it, think about something else for a while. Then, when you come back to it, you will have a fresh perspective, and you will be better able to find the flaws in your writing. Now put it away again, and so on. After a few cycles, you will find fewer and fewer things to change, which is an indication you are nearly finished. For myself, I remember the day I looked at a well-written passage and realized I hadn’t supplied the citation. I spent hours searching for the quote, only to discover I had written it myself. When I was able to stop being hyper-critical and finely appreciate what I had written — that is when I knew I was done.

Now go forth and do likewise.